One of the common objections I’ve heard to adopting Model-Based Systems Engineering (MBSE) is that it is prohibitively expensive. The tools used to perform MBSE are more expensive than tools previously used to perform Systems Engineering. The costs associated with training an existing Systems Engineering workforce in the methods, semantics (languages such as UML or SysML), and tools (i.e., MagicDraw, Rhapsody, Enterprise Architect, etc.) necessary to implement MBSE practices on a large scale are not insignificant. For a lot of people it’s easy to make the claim that there is not room in any single project’s budget to justify the investment required to adopt MBSE when their organization already has practices in place that are “good enough.”

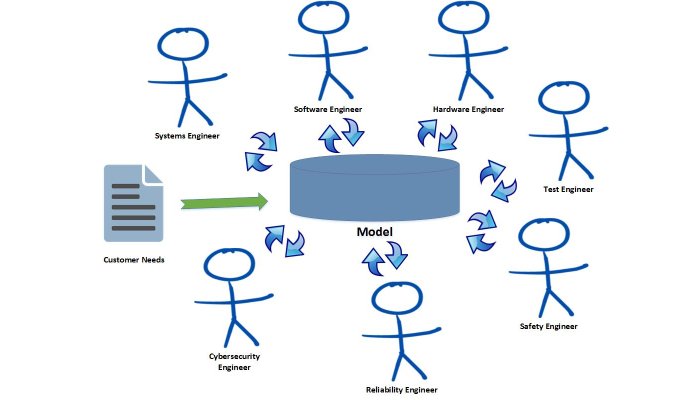

The typical assessment of the impact that adopting MBSE will have a project’s bottom line fails to take into account the hidden costs of not performing MBSE. In the development of modern complex systems there are typically many stakeholders. Having spent my career in the Aerospace and Defense industry, I can tell you that when a new aircraft is being developed, stakeholders include but are not limited to; Systems Engineers that define system requirements and interfaces, Software Engineers that write the code that runs the system, Hardware Engineers that design the parts from which the system will be composed, Test Engineers that will verify the system operates as specified, Safety Engineers that analyze the safety risk of the system, Cybersecurity Engineers that analyze the system’s susceptibility to threats, and Reliability Engineers that validate the system meets the availability needs of the customer. Each of these stakeholders has unique objectives that will potentially impact one or more of the other stakeholders. Further, each of these stakeholders must take into account the context in which their analysis is being performed, and they must have a certain level of understanding about the architecture of the system.

While they’re not always referred to as use cases, when a stakeholder puts their analysis into context they often do so using some form of a use case (they can be referred to as sequence diagrams, operational scenarios, functional flow block diagrams, etc.). Additionally, their architectural concerns are usually documented in some kind of block diagram. Once the stakeholder has created a use case to provide context to their analysis, and created a block diagram to document their architectural concerns they typically derive some requirements that may at some point be injected into some kind of requirements repository. What’s expensive about this is that when an organization is not using MBSE the work of creating use cases, block diagrams, and then deriving requirements lends itself to a lot of redundancy. While each stakeholder will express their own concerns, the use cases and block diagrams they’ll create will typically communicate a lot of the same information, which means multiple stakeholders will be redoing the same work.

When MBSE is used properly all stakeholders can refer to a single model that documents the context and the architecture of the system. Rather than each stakeholder duplicating work by created completely new use cases and block diagrams, they can update a model that is maintained by an architect to express their concerns and document the results of their analysis. This means that the opportunity for cost savings increases with every additional stakeholder that treats an architecture model as their primary artifact.

While the upfront investment of adopting MBSE is significant, the savings realized by reducing the amount of duplicate work performed by multiple stakeholders during the development of complex systems can greatly outweigh the investment when MBSE is implemented in a practical manner.